BD Platform

Security Operations, Accelerated.

A step-by-step breakdown of how to untangle an 11,000-line JavaScript credential stealer. Follow along as Binary Defense Deputy CTO John Dwyer decodes the chaos—revealing how to extract payloads, capture IOCs, and turn a mess of obfuscation into actionable threat intelligence.

Obfuscated JavaScript stealers are noisy, messy, and intentionally frustrating, the kind of samples that make you want to throw your debugger out the window and go home. This post walks you through one of those beasts step-by-beast: a ridiculously long, heavily obfuscated credential stealer that, once decoded, spills out URLs, filenames, commands, and everything an analyst needs to hunt and remediate. You’ll get a paired video walkthrough plus a written, copy-pasteable playbook so you can follow along in your debugger and reproduce the entire decode pipeline.

These infostealers don’t just hide in plain sight, they bury themselves beneath stacks of tiny decoder functions, lookup tables, and a state machine that only makes sense when it runs. That means staring at the file won’t get you far; you have to run it and watch what it does. If you can reliably pull out the decoded strings and rebuild the payload, you’ll be able to collect IOCs faster, write hunting rules that actually catch the behavior, and produce cleaner detection signals... plus it’s oddly satisfying to turn a mess of obfuscation into something you can use.

Threat Family: Supreme Stealer

Language: JavaScript (Node.js-compatible)

Malware Type: Infostealer / Credential Theft

Sample: https://www.virustotal.com/gui...

Attribution Evidence: The decoded runtime constants contained the developer tag '@Supreme_Stealer ~ v', which is a known indicator for this malware family. The decoded configuration also matches previously analyzed Supreme Stealer variants with overlapping command-and-control (C2) infrastructure and exfiltration URLs.

The malware uses extensive obfuscation through dynamically generated lookup tables, encoded string arrays, and custom character-based base-N decoding implemented through chained functions (WM, WL, WX, WK.decode). Runtime string decoding occurs in memory, with plaintext strings only existing momentarily before execution. Anti-analysis behavior includes references to process names associated with debugging and reverse-engineering tools (e.g., Fiddler, Burp Suite, Wireshark, IDA, OllyDbg), which the malware may attempt to terminate or avoid.

The JavaScripts builds large lookup arrays (WS, WL, WM, etc.) and a state machine (many switch/case blocks where index arithmetic decides flow).

There are many tiny functions with reused names like WK, WM, WX. At runtime the loader uses the current scope’s binding (the one visible where the code runs) to decide which function is used.

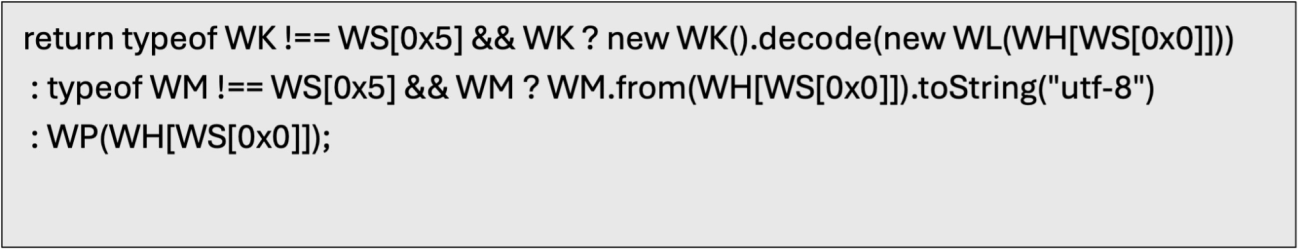

The final decode call often looks like a ternary/fallback chain, for example:

In plain terms: if WK is a usable constructor, call new WK().decode(..); else if WM is present use WM.from(...).toString('utf-8'); otherwise call WP(...). That sequence is simply ordered fallbacks.

The useful results are assembled later into a big WM array of tokens (strings) — once you extract WM you get the malware’s readable artifacts.

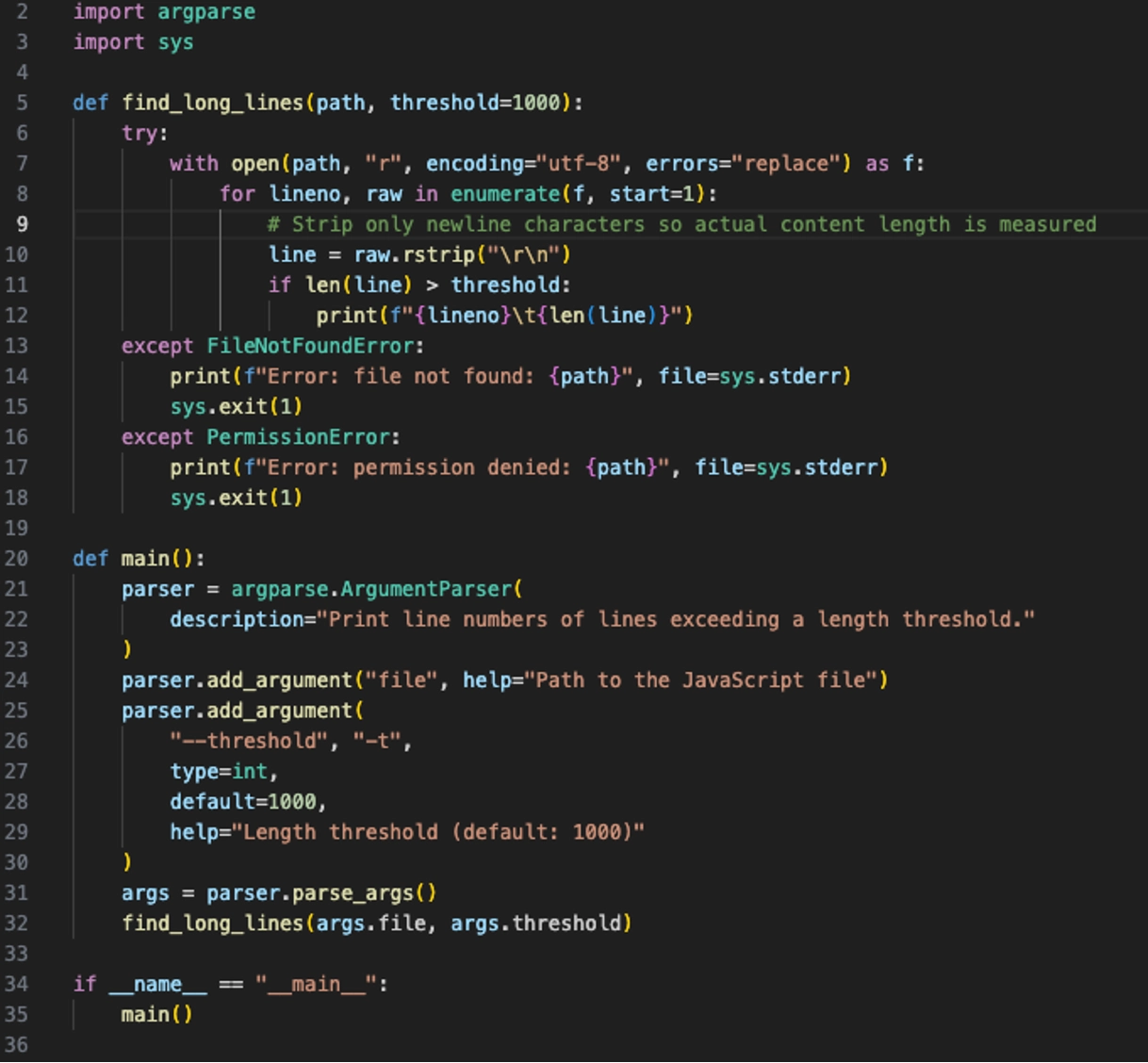

Identify long lines – simply running a count and identifying any lines that have more than 1,000 characters is a great way to find where encoded data is stored in the script. This will allow the analyst to make notes of variables which contain encoded data used by decoding functions.

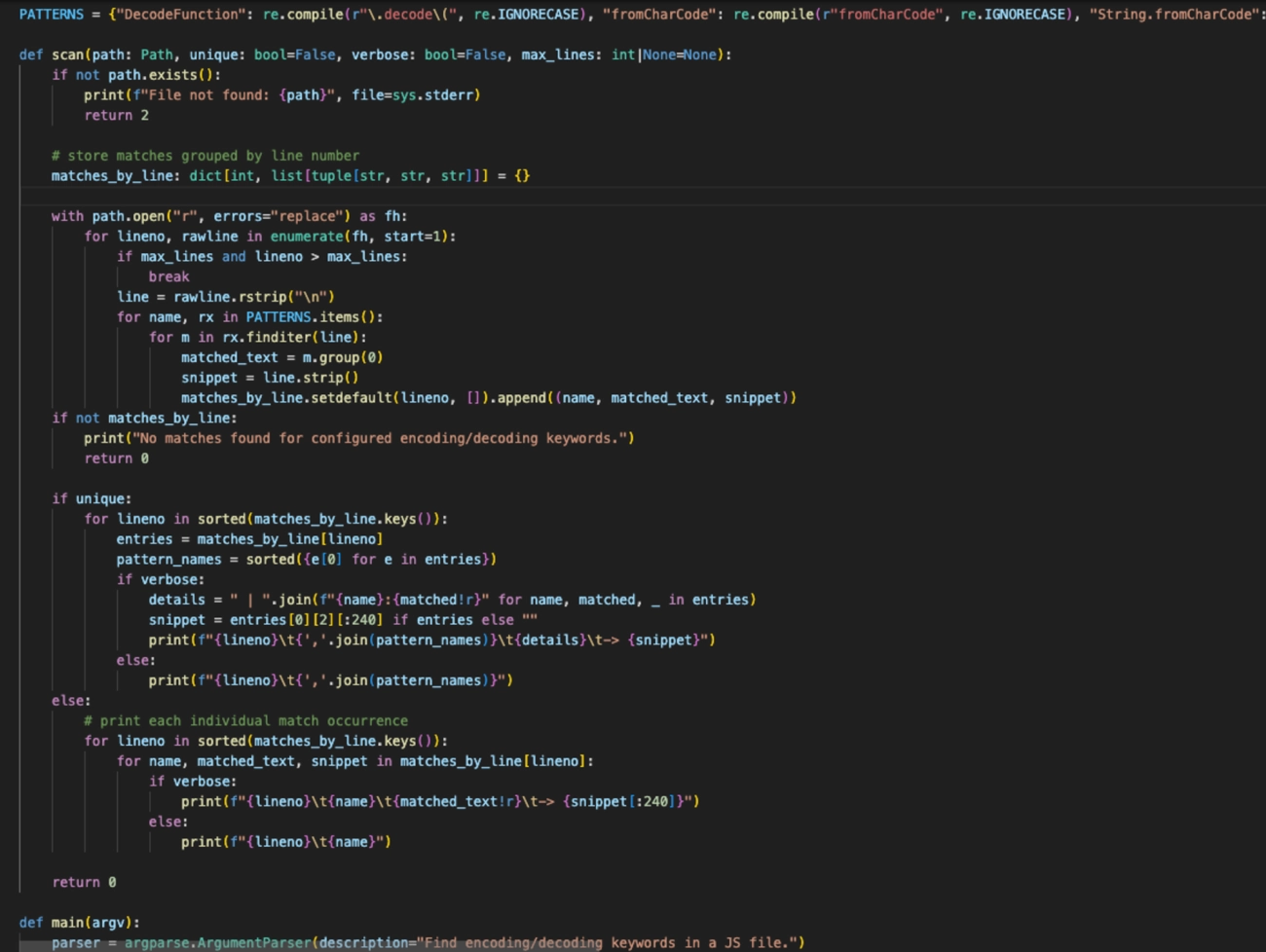

Scan the code for common decoding/deobfuscating commands such as “.decode”, “atob”, “btoa”, etc. Native decoding commands are often used in these JavaScript samples, so just identifying where these commands are used in the script is a great place to give analysts a starting point.

Locate the decode hotspot. Put a breakpoint on the return line that does the decode/from(...).toString(...) fallback. This is where decoded text surfaces, regardless of which helper function earlier executed.

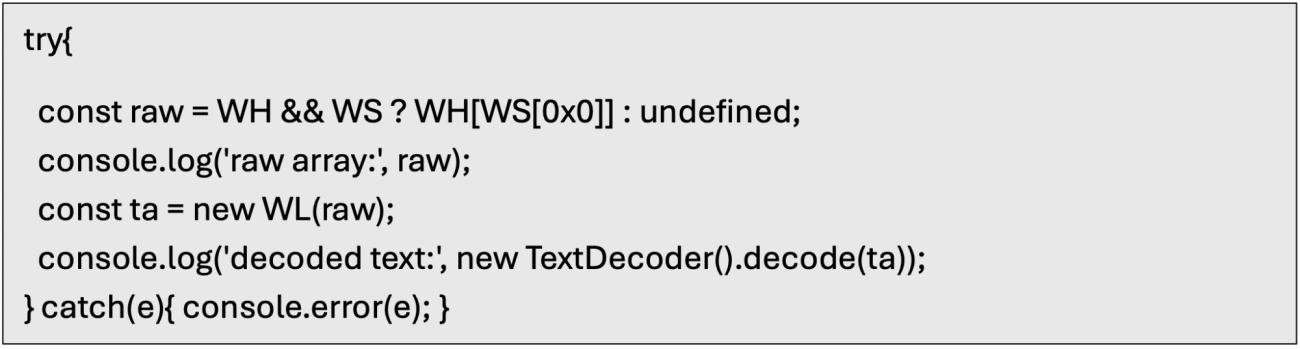

When paused, inspect the locals. Check WH, WS, WL, WK, WM in the Scope pane or console.log() them. If you see a Uint8Array/array, decode with TextDecoder to preview

Manually decode the returned data using the native JavaScript decode() function

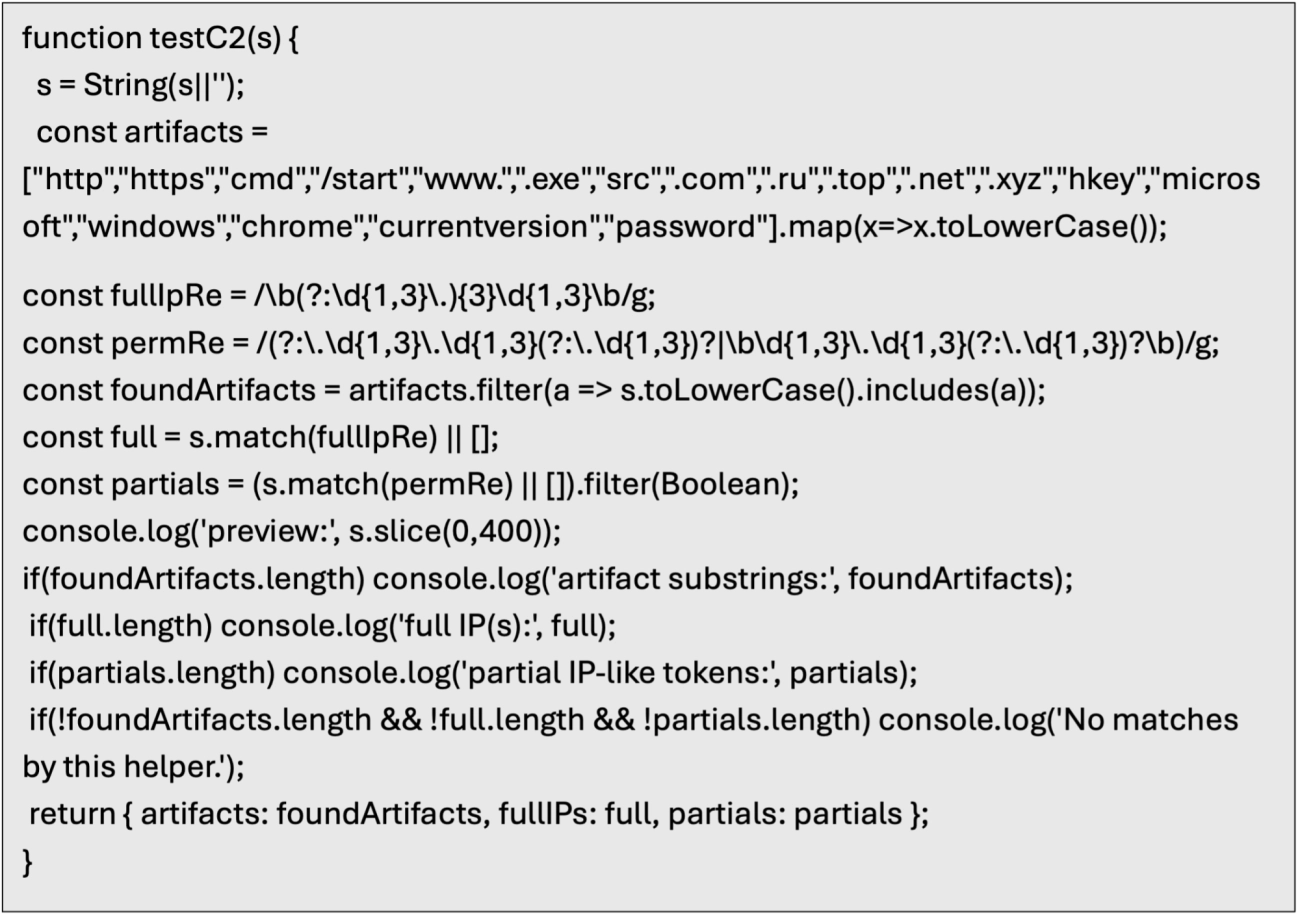

Scan the returned values for common C2 keywords such as IP addresses, domains, common OS directories, etc using a JavaScript debug function

Add TestC2 Function to Debug Console

Add conditional break point to the .decode() line with the following expression to flag any hits again TestC2

Restart debugging session and set breakpoint on .decode() line. Let the script continue (F5) several times (around 15) until you are in the main part of the decoding loop.

Step into the code until you reach the function where the return value is WL.

Continue stepping into the code until you reach the line where const WM is updated with the values of WL.

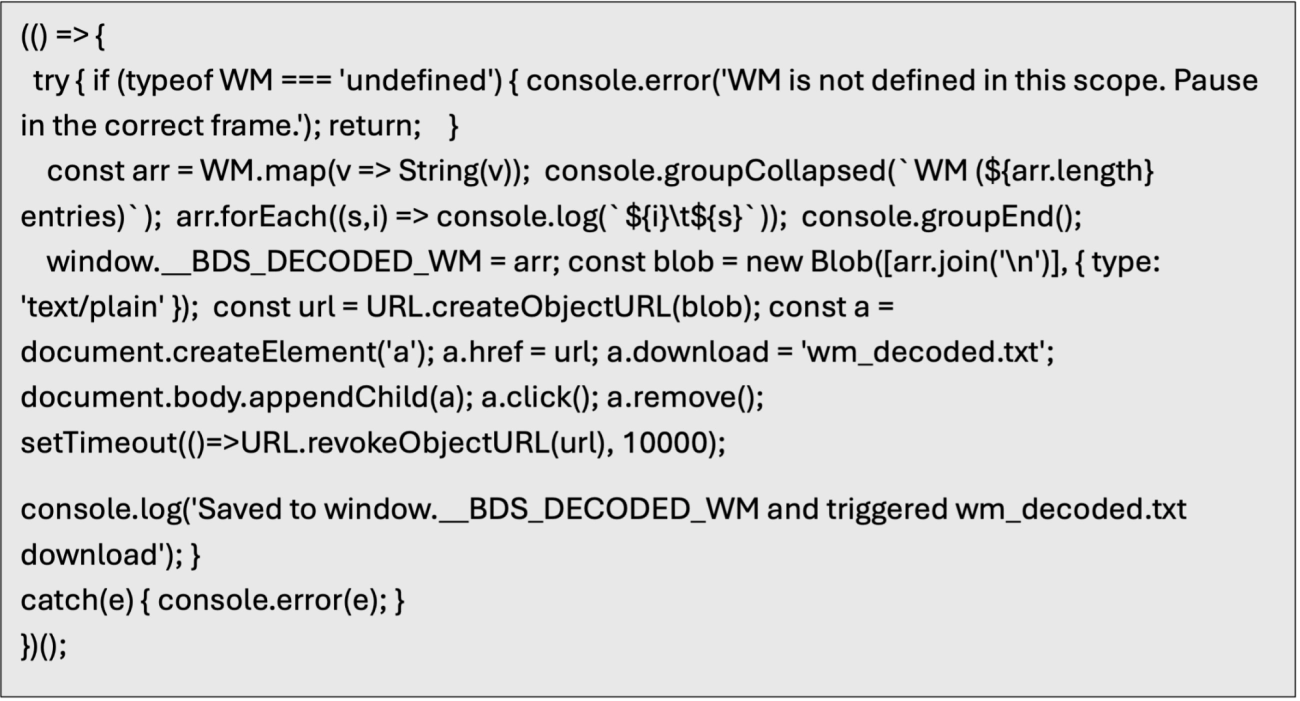

Set a break point after WM is completely updated and then use a JavaScript snippet to loop through WM and save the contents to a file.